Can you slingshot at $c$?

The question is simple enough, could we use a gravitational assist to pull off a manoeuvre that would fling our spacecraft out of a hyperbolic trajectory at near light speed?

Let’s take a look.

Imagine you’re coasting around a planet with a mass that is large enough to cause a non-zero \(T_{\mu v}\) and would like to perform a slingshot using gravity assist to get some traction for your next destination. As part of the escape hyperbolic trajectory where your spacecraft is moving relative to the massive object you’re about to exploit, you’re to be moving at non-relativistic velocities as at relativistic speeds you cannot be in a hyperbolic escape trajectory. From a basic standpoint, we usually recommend that objects (mainly satellites) need to reach escape velocity to leave the Earth’s orbit, but objects do not need to ever reach earth’s escape velocity of 11,186 m/s, and many that leave orbit don’t. It mainly depends on where the object is when it needs to reach 11,186 m/s. But with gravity assists, or flybys depending on the velocity vector and flyby position of the spacecraft, when observed in the reference frame of the Solar System (fixed to the Sun), the benefit of this manoeuvre is made apparent. The probe gains speed by acquiring energy from the speed of the planet as it orbits the Sun or star by flying along the movement of the planet, thereby gaining some of the planet’s orbital energy in the process and to decrease speed, the spacecraft flies against the movement of the planet to transfer some of its own orbital energy to the planet (If the trajectory passes in front of the planet instead of behind it, the gravity assist can be used as a braking maneuver rather than accelerating). The sum of the kinetic energies of both bodies remains constant due to elastic collision, and can therefore be used to change the spaceship’s trajectory and speed relative to the Sun.

How flybys work?

Here’s NASA’s drilled down explanation.

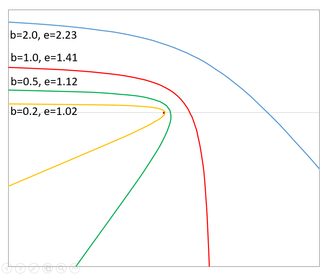

With a hyperbolic trajectory the orbital eccentricity (\(e\)) is greater than 1. The eccentricity is directly related to the angle between the asymptotes. With eccentricity just over 1 the hyperbola is a sharp “v” shape. At \(e=\sqrt {2}\) the asymptotes are at right angles. With \(e\gt2\) the asymptotes are more than 120° apart, and the periapsis distance is greater than the semi major axis. As eccentricity increases further the motion approaches a straight line.

The angle between the direction of periapsis and an asymptote from the central body is the true anomaly as distance tends to infinity \(\theta_{\infty}\) so \(2\theta_{\infty}\) is the external angle between approach and departure directions (between asymptotes). Then,

\(\theta{_{\infty }}=cos^{-1}(-1/e)\) or \(e=-\frac{1}{cos\theta_{\infty}}\)

When coming to a flyby using gravitational assists, the object would need to enter against the massive body’s motion and exit with it’s acquired orbital energy at an angle. When flown in a hyperbolic path the craft can flyby without any additional acceleration from it’s engine, which further saves a bit of fuel. A pretty good flyby can be achieved if we minimise \(\theta\) between the massive body and the spacecraft’s exit path given by \(\theta=cos^{-1}(1/e)\) where \(\it e\) gives the eccentricity of the orbit and must be \(e\geq1\). Now, the ideal path to follow would be as we see \(e\rightarrow\infty\), the trajectory would be orthogonal to the body’s orbit, and no assist would be obtained, therefore a parabolic trajectory would ensure the path would be in line with the body’s orbit and as the velocity increases the \(\it e\) would increase which we don’t want as seen from the flight path angle given by, \(\tan(\phi) = \frac{e.\sin\theta}{1 + e.\cos\theta}\) and velocity from \(v = \sqrt{\mu\left({2\over{r}}-{1\over{a}}\right)}\), where:

- \(\mu\), is the standard gravitational parameter

- \(r\), is radial distance of orbiting body from central body

- \(a\) is the (negative) semi-major axis.

Hyperbolic paths followed by objects as they approach the central object with the same hyperbolic excess velocity and semi-major axis=1 but different \(e\) and impact parameters

And from \(v^2 = v_{esc}^{2}+v_{\infty }^{2}\) we get orbital velocity (\(v\)), local escape velocity (\(v_{esc}\)), and hyperbolic excess velocity (\(v_{\infty}\)), even a relatively small \(\Delta {v}\) above \({v_{esc}}\) yields us high excess speed of \(v_{\infty}\) which is the Oberth manoeuvre that uses additional acceleration by falling into the gravitational well of the body (for heavier object such as black holes this would employ general relativity where the gravitational potential would change to a metric tensor). Using the heavy body, our sun for example if used conduct one burn at periapse, and get a significant boost above and beyond the \(\Delta {v}\) of the burn, but you’ll still need something much more massive to approach the speed of light. So unfortunately for non black hole like bodies such as planets or even stars, this wouldn’t result in much orbital trajectory deviation and nil transfer of momentum and velocity gained will be mediocre.

This changes for objects with high densities such as neutron stars and black holes. If you’ve watched the film ‘Interstellar’, the techniques used to pull of flybys are still conditional and require a binary star system that are orbiting each other, and that the spacecraft which you’re in happening to traverse from source to destination from one star to another. Kip Thorne theorises the slingshot around the supermassive black hole, through which the probe could attain enough kinetic energy even which cannot be affirmed to be close to ~ 0.5c. There’s the concern of the limit our probe can hover within the Schwarzschild radius, \(r\) and as we get closer to \(r\) we can’t exactly determine that at \(r=6M\) from $r_s=(\frac{2GM}{c^2})$ we would use the slingshot, or if we could go further closer, and calculating the minimal orbit radius for an unknown binary star/black hole on the fly would be non deterministic and our desired hyperbolic or parabolic trajectory is hard to maintain as one moves closer to the event horizon where orbits run periodic. This complicates issues further as we leave Newtonian gravity and delve into the two-body problem in general relativity, Schwarzschild geodesics, and the remote risks of falling into the event horizon beyond which, realistically, would end up in the singularity.

The specific energy \(𝐸̃\), and the allowed range of radial coordinate would correspond to where \(𝐸̃\) is constant, a trajectory that starts at infinity and ends at infinity would correspond to the case \(𝐸̃_2\) in the image, it would have a turning point at some value of radial coordinate larger than unstable circular orbit (\(𝐸̃_{max}\) in the image) but unstable circular orbits lie within the interval \(3/2𝑟_𝑠\)<\(𝑟_{uco}\)<\(3𝑟_𝑠\) from the photon sphere to the innermost stable circular orbit for any point less than 1m from the event horizon would be in the photon sphere. For a non rotating black hole, the geodesic motion of a test particle has an effective potential which typically (for some value of specific angular momentum) looks like:

Hypothetically, for a trajectory to approach within 1m from event horizon it must be either of the type \(\tilde E_3\) or \(\tilde E_4\). \(\tilde E_3\) corresponds to the trajectory of the particle falling into the black hole, while \(\tilde E_4\) is a geodesic that starts and ends on the horizon. For specific values of the angular momenta, only one circular orbit can exist for one value at the minimum of the curve. If the energy drops (due to friction, engines, etc.) for \(\tilde E_1\) the elliptical orbit, the angular momentum would also drop, the above would change in such a way that the orbit becomes closer to \(\tilde E_{max}\). The \(\tilde E_1\) orbit is conceptually the same around the Earth or a black hole, if the energy on an elliptical orbit drops, the orbit essentially becomes closer and if the energy drops further, the objects hits \(\tilde E_{max}\) and goes down. In a Schwarzschild black hole, stable circular orbits are only possible in the region \(𝑟>3𝑟_𝑠\), the radius of the ISCO, while in the range (from photon sphere to the ISCO) 1.5\(𝑟_𝑠\)<\(𝑟<3𝑟_𝑠\), there are unstable orbits. So structure and stability of orbits from a Newtonian perspective does not necessarily hold for highly relativistic orbits near the horizon, it is possible to have stable orbits within the ergosphere of a rotating black hole though only at high spin parameters \(𝑎\) (\(𝑎/𝑀≳0.9\)) (stable circular orbits in the ergosphere for \(𝑎≳0.9𝑀\)) i.e. rapidly rotating holes.

Example of a test particle in a circular orbit inside of a black hole with spin parameter a, at energy r and a local velocity of c

In summary, looking at just Newtonian style orbital mechanics, the spacecraft could approach very close to the center of mass of the planet, and experience a large change in direction which could transfer kinetic energy from the planet’s orbital speed to the spacecraft, and too close an approach would result in tidal forces that could rip it apart and if moving at relativistic speeds it wouldn’t have much of an effect. Basically, we don’t know, yet if it’s possible to perform flybys at near $c$ as it depends on the mass and angular momentum of the massive body, and velocity reached by the probe also varies with the rate of propulsion of itself when moving along the hyperbolic path and ideally without firing the engines. Ever expanding universe notwithstanding, exploring new realms of energy generation and storage such as tokamak fusion engines and the like could achieve significant strides in non-trivial space travel, although we’re in it’s infancy and before we can send out humans into such vast distances, we would already need to have non-human probes in place capable of interstellar travel through long periods of testing and observation.

The Voyager mission probes are the best examples of long standing probes that have successfully enjoyed gravity assists to push forth incredibly vast distances for forty plus years, and they took a long time (still remarkable) to reach the edge of the heliosphere. Before we can think about warp drives, wormholes and other sci-fi systems, or the more grounded Alcubierre drive there are probably a few more equations we need to solve. Space is vast and all we can do is put down our heads, calculate, find new tricks, observe and send out better vehicles if we want to to traverse light years with close to light speeds, or can we do FTL?

Some interesting links: